❄️Cryo

Cryogenic propulsion in DARE

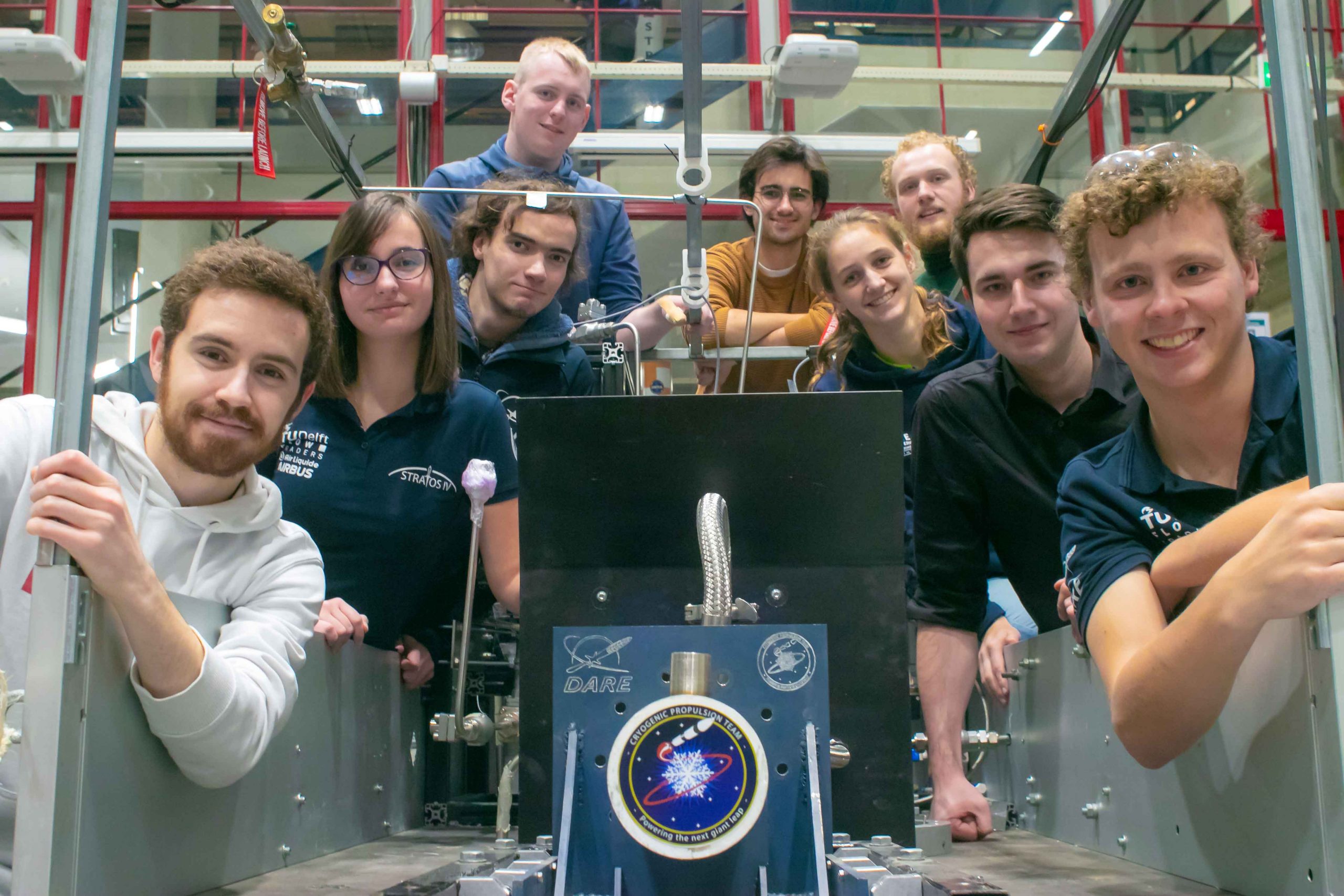

When I went to the TU Delft for my BSc degree, it was mostly for two reasons; I wanted to experience an international environment and build rocket engines. Luckily for me, I got to do both things! I quickly joined the student society Delft Aerospace Rocket Engineering (DARE) and specifically the newly formed Cryogenic Propulsion team (CRYO). We wanted to built on the experience of a liquid propulsion project called Deimos Deimos which proved that a student teams can tackle the challenge of more complex propulsion systems. Still, much of the talent in Deimos finished their studies and the CRYO group was mostly fresh, and very exited, younger students which were let loose to work on a liquid oxygen (LOX) and ethanol rocket engine. Starting out, we had big dreams but pretty much no equipment that would be needed to build a bi-liquid and even less so a test site which could house our dreams of 14 kN engine. For me those dreams lead to a six-year journey that started with leaky pipes and valves, and is now being carried on by the next generation of students in DARE. Oh, and along the way we designed, built and tested plenty cryogenic rocket engines, and now it is looking like those engines might just carry our dream to space and low-earth-orbit.

Let’s take some steps back, and I’ll share some of the experiences that stuck with me the most. But before diving into stories of LOX socks and the octo-box, I want to focus on one thing that has become very important for me over the years; rocketry is dangerous and the consequences of failure can and will be deadly. The sad passing of a young enthusiast in the US just a year before I joined DARE, serves as a reminder of the unforgiving physics of space flight. The thing I am prouder of than any achievement within DARE is our attitude to safety which lead to 22 years without a single serious injury. Our DARE safety officers & trainees who make it their mission to protect us from ourselves each and every day deserve the highest praise that anyone can give.

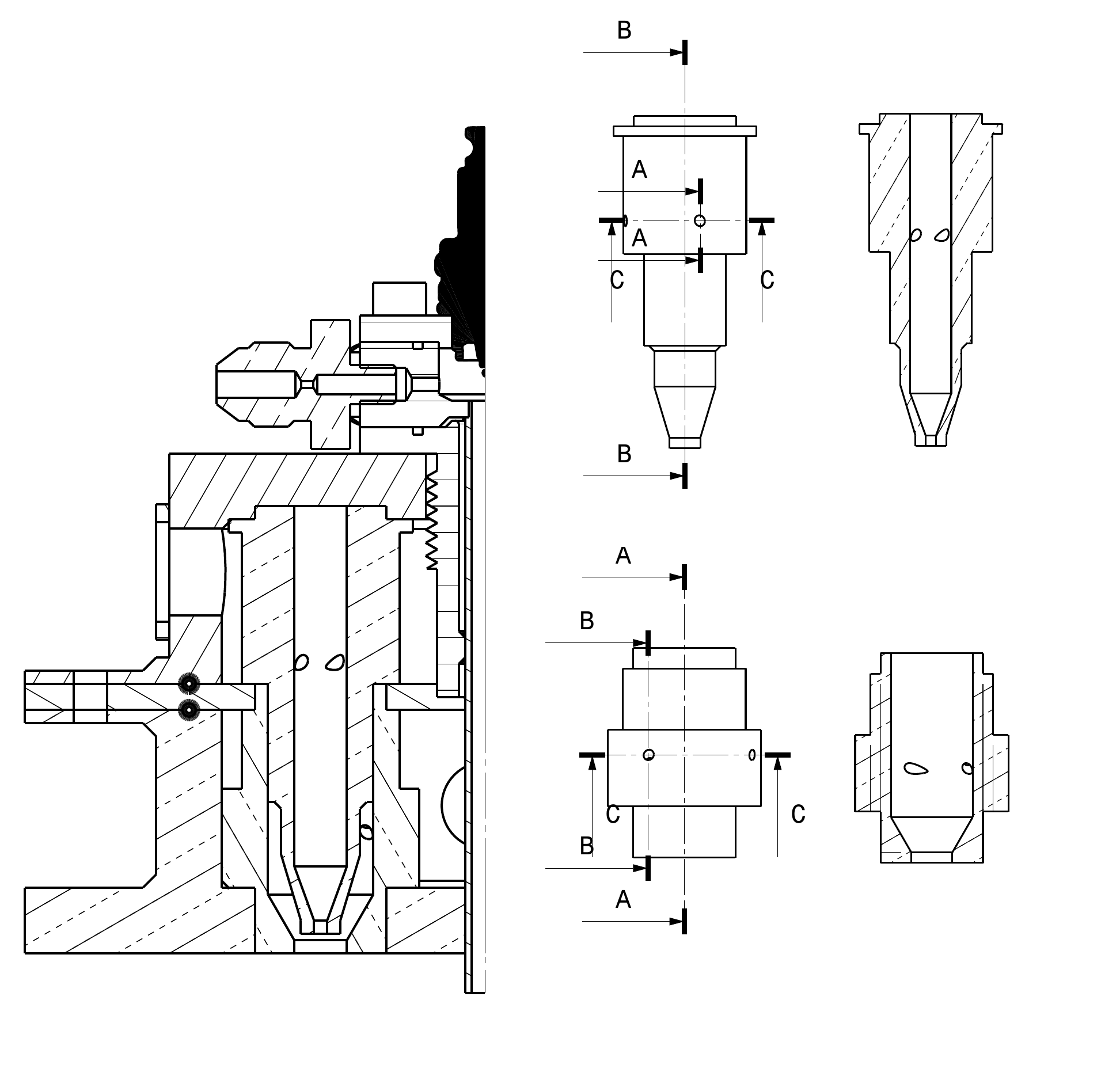

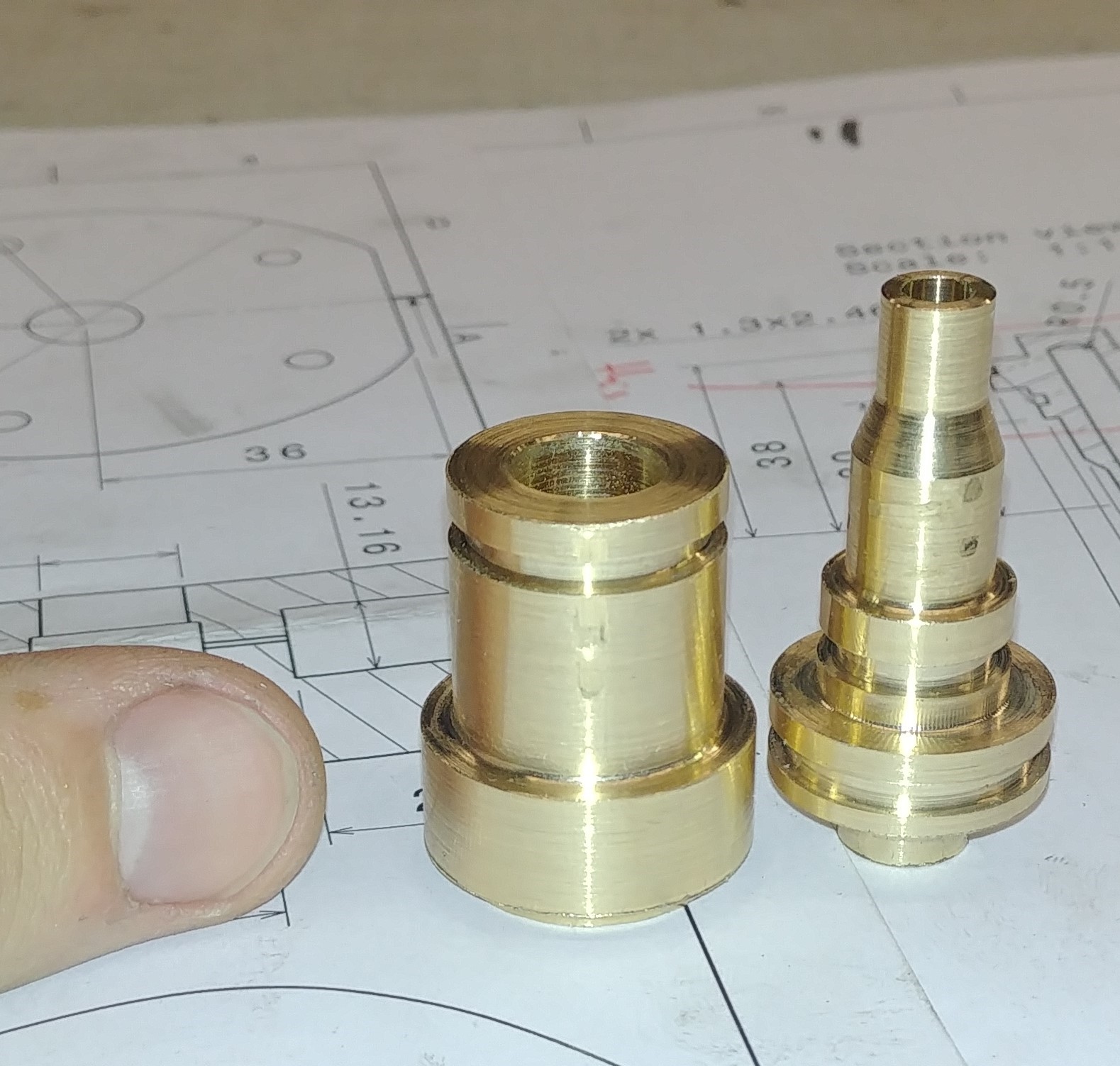

With that being said, lets jump into my first project; the easy and straightforward task of designing a coaxial swirl injector for our LOX-ethanol engine. Together with my good friends and colleagues Andrew and Nick, we immediately violated Akin’s 26th law of spacecraft design and started the design of one of the most difficult parts of an engine, choosing a notoriously tricky option. Not to be deterred by our own admittedly limited abilities (sorry lads), we popped out a design and planned our first test. But to test we would need to produce the parts for our design first. Long story short, we did in fact end up with a prototype system, and the memory of working a whole weekend on a manual lathe and mill on a coaxial element just for us to mess up the last operation will forever be with me. I promise you, if you stare long enough at a broken drill bit stuck in an aluminium piece the aluminium stares back.

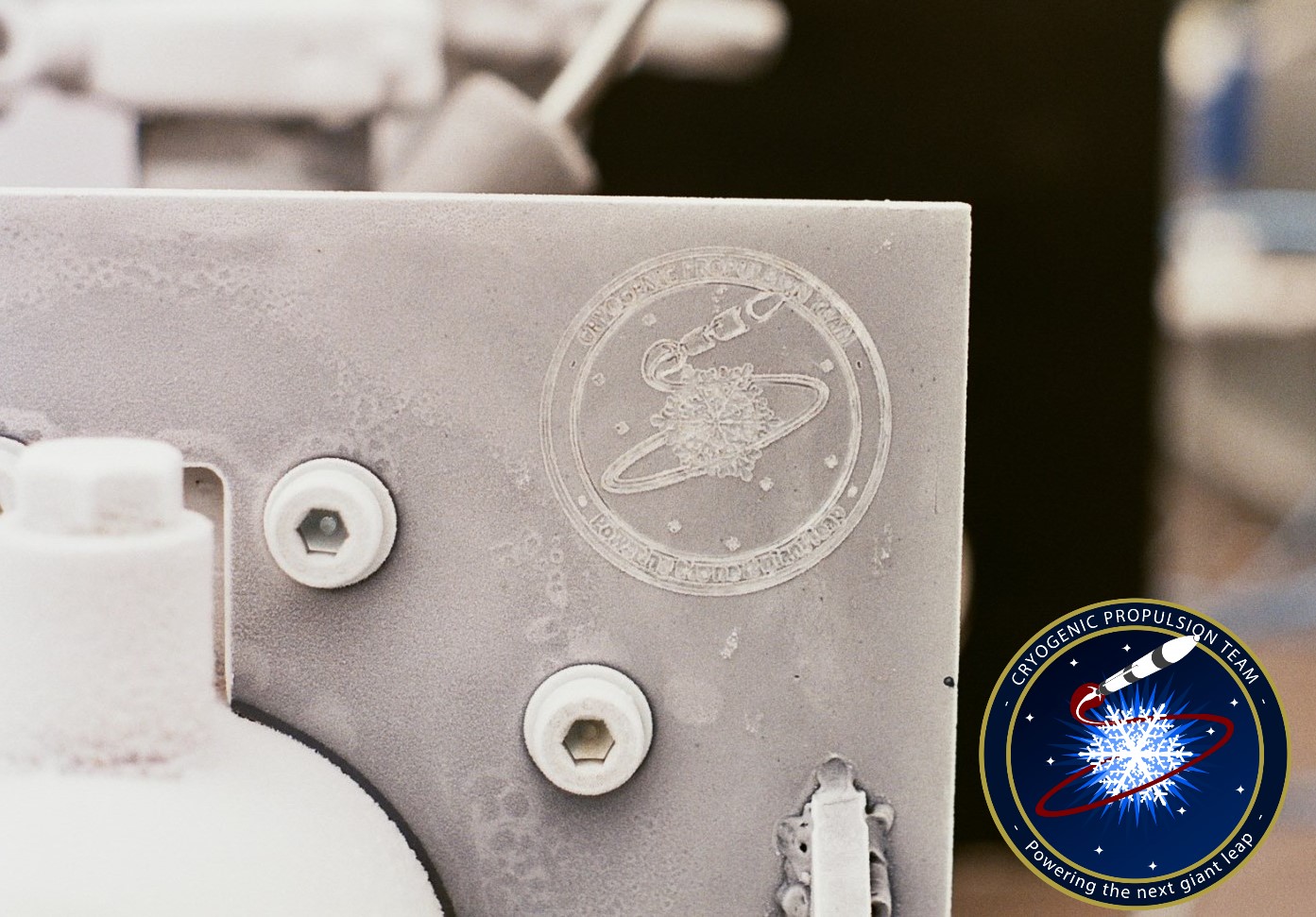

Finally testing the prototype on CRYOs full engine setup did feel a lot like growing up, and I hope my co-conspirators know that I will forever treasure our time on this project. Still, we learned from our first encounter with Akin’s laws and decided to prove his fourth law right for our next trick. CRYO and our “Blizzard” engine was making quick progress, and soon we found ourselves handling LOX and putting some elbow grease into getting our system ready for hot fires. I am also glad to mention that my friends’ talent and experience was growing in equal measure to their leadership abilities, and they were able to pick up the heavy burden of coordinating the flock of overexcited geese that was us. Naturally, we immediately had to spend several days around ultrasonic cleaning equipment and acetic acid scrubbing all that elbow grease out again. LOX can ignite on contact with carbon compounds.

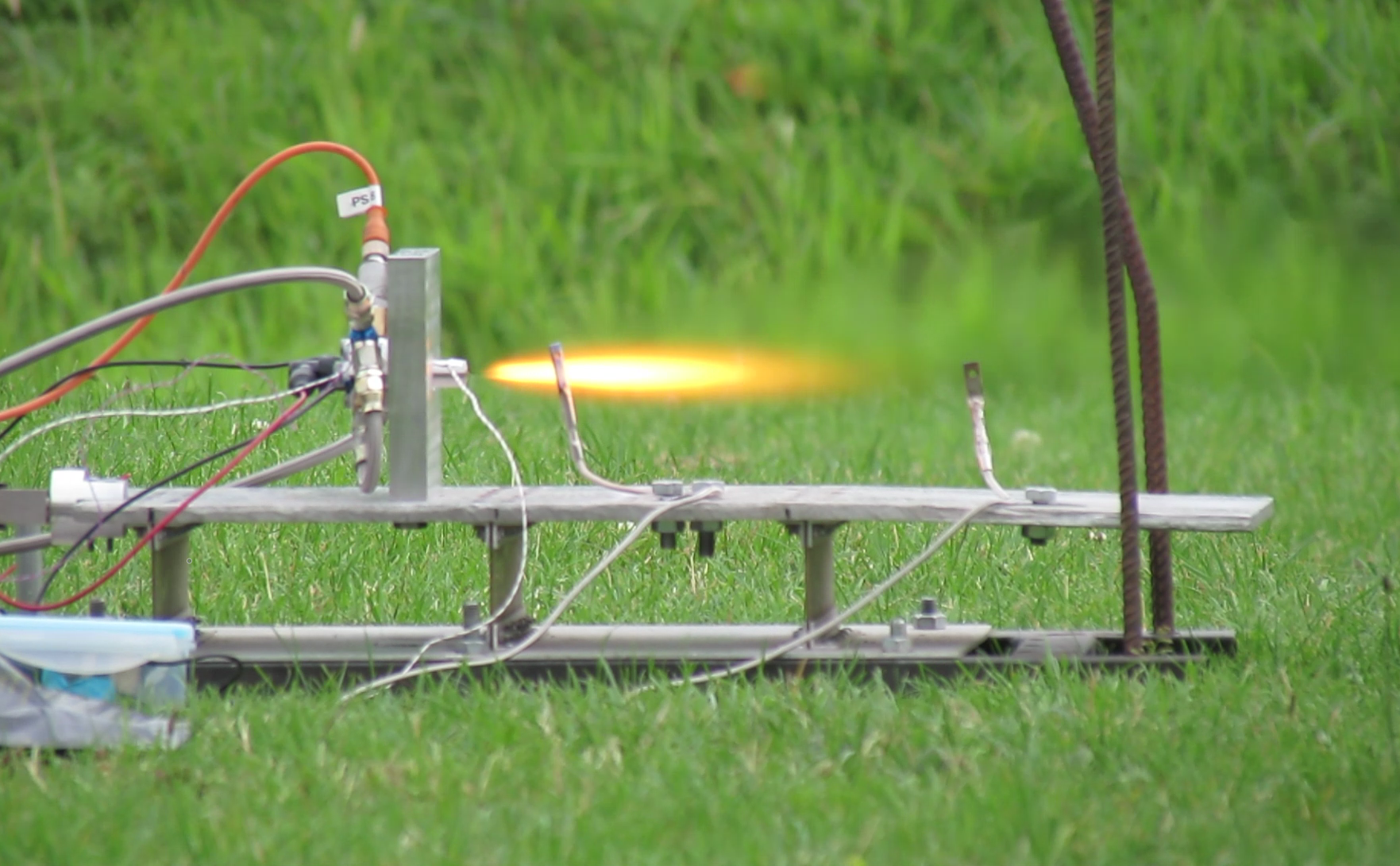

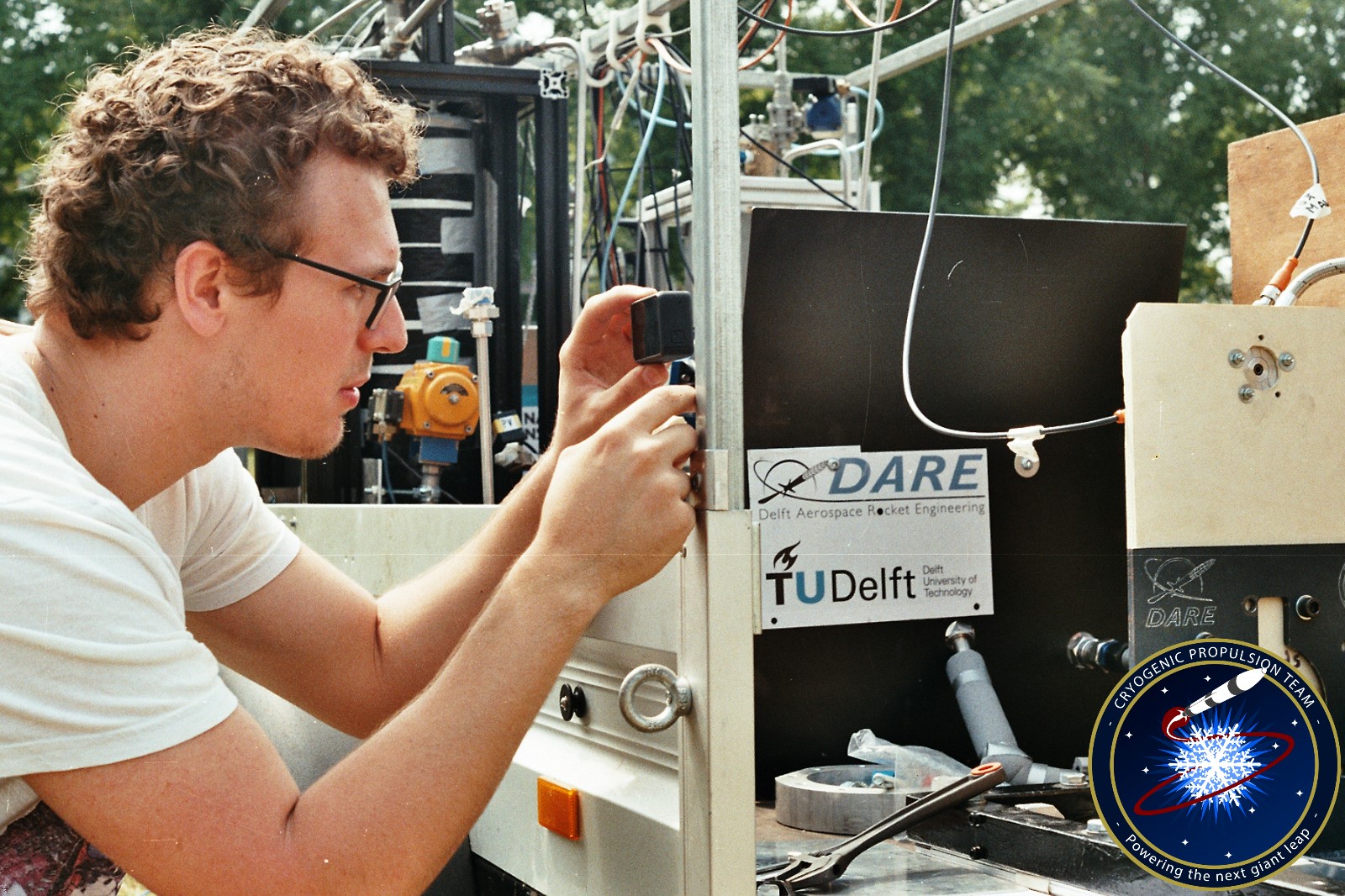

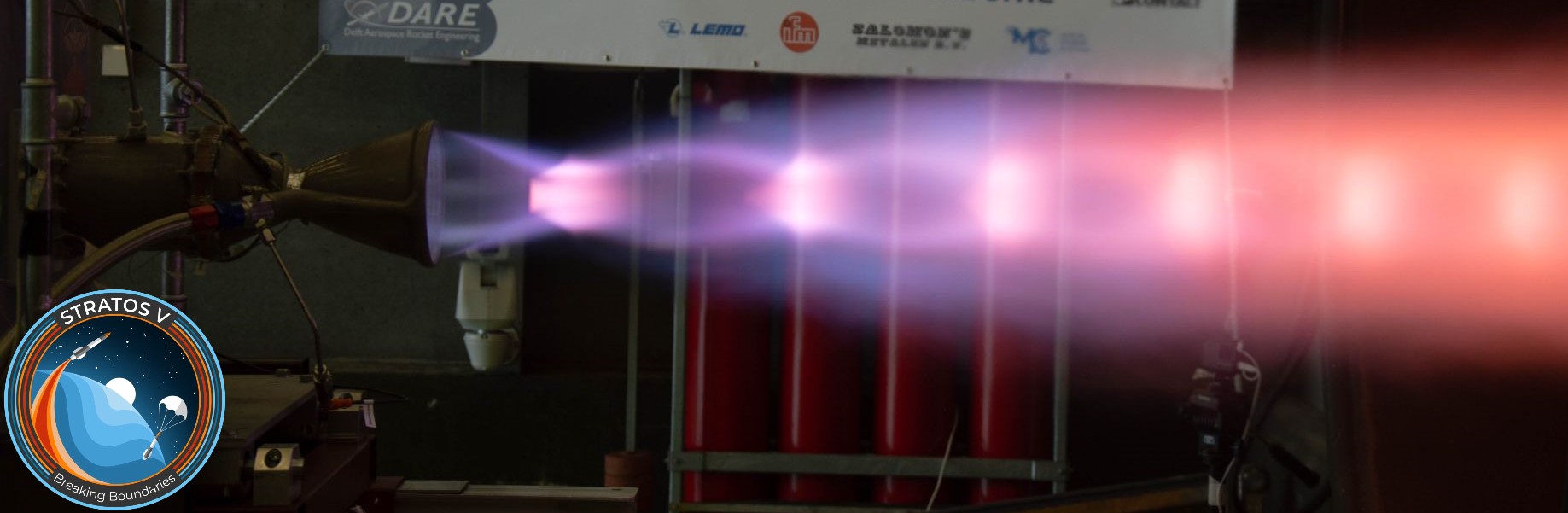

Now we meet the nemesis of this page; rocket engines! To properly test these jerks (we call it a hot fire, because they produce fire, which is hot) you need to be safely away from them and have some way to deal with the exhaust, noise and possibility of a rapid unscheduled disassembly event (boom). The thing that was immediately clear to us is that the Netherlands is not host to wide empty fields without protected bird species. The only place we were ever going to light this thing was wherever the Dutch F-16s fighter jets were tested. Still, even there we were quite concerned that we are going to blow both the F-16 test stand and the Dutch military maintenance budget wide open. However, before CRYO managed to aerate any government property, the team made an important step forward: the previous DARE flagship project was finishing up, and CRYO was picked up by a lot of very talented people who were working towards turning the project into a full-time affair. While I do not have the ability to properly honor all the incredibly dedicated people that went on to contribute to the success of this project I want to at least mention my good friend Jonathan who is, plainly, one of the best engineers I have had the pleasure of working with. This brings us to Project Sparrow AKA the mad lads who actually did it. They actually did it.

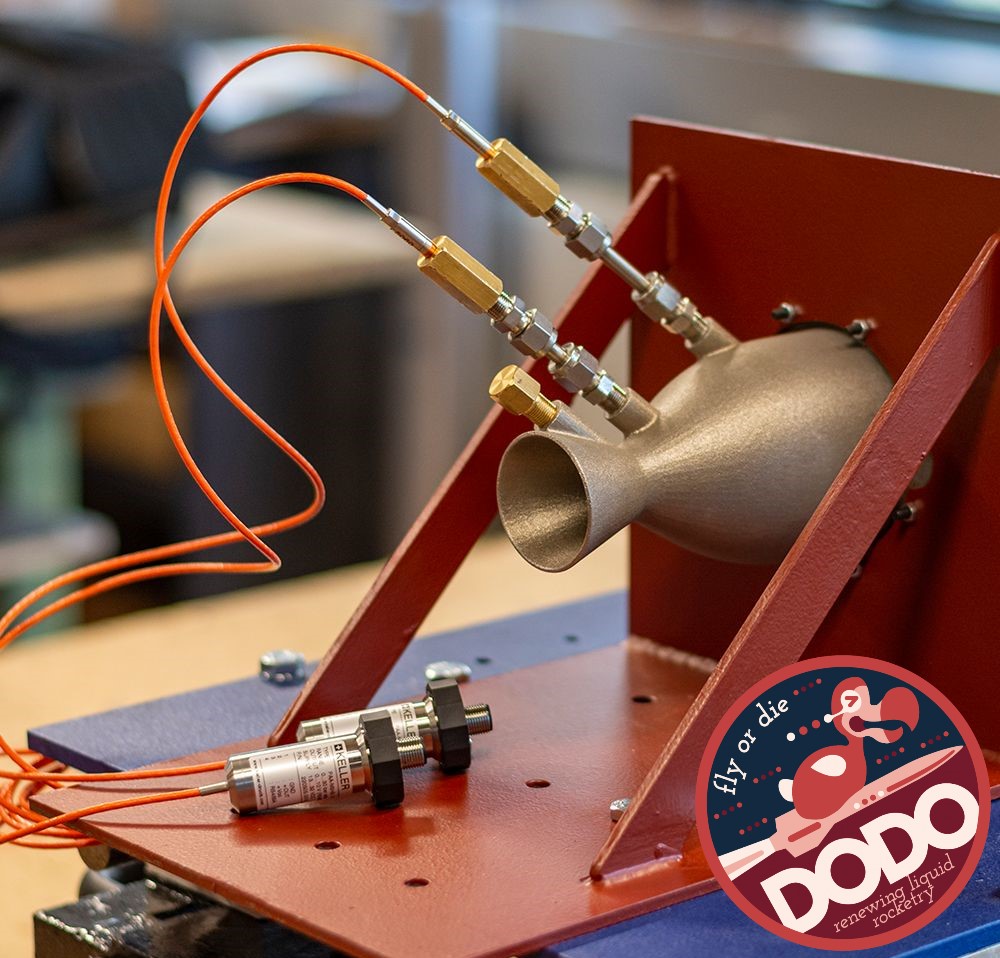

Now, while the story of liquid propulsion within DARE is far from over, my small part within its history is since I decided to turn towards exoplanet science. While I contributed to and supervised some more projects (e.g. Sparrow & LOX electric pump), Sparrow, Stratos, Dodo, and DARE EuRoc are carrying the torch on. I have the highest confidence in the talented people that have shaped, and will shape the future of human space travel, and wish each of them the best. Whenever a launch vehicle carries one of our telescopes to the emptiness of space, we do well to remember that it was not the machine, but the people who carried us. Thank you, you will always be in my heart.