Curios RL

Intrinsic curiosity and motivation in deep reinforcement learning

Are machines curious?

In Deep Reinforcement Learning (RL), we often design or choose a reward function that rewards RL agents for good actions. However, what if we do not know what good actions are, or can only assign them if very specific conditions are met? If we do not reward RL agents, do they develop intrinsic motivation to explore and can their curiosity help us develop systems that can autonomously develop long-term strategies where good (or bad) outcomes cannot be easily defined?

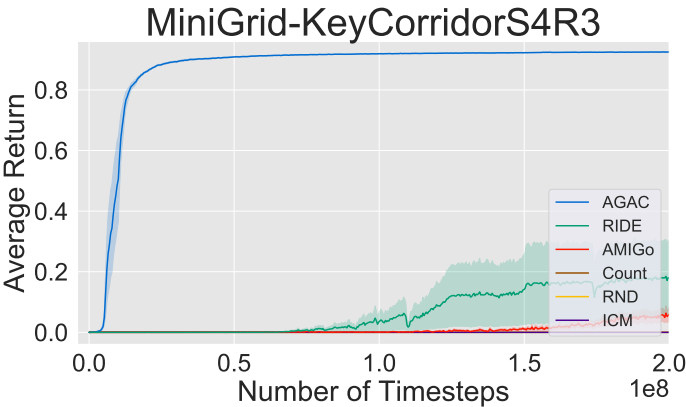

In the 2023 Advanced Seminar on Deep Reinforcement Learning given by Tomas Moerland and Aske Plaat (Scientific Director at LIACS), I got to explore these questions and developed an information-theoretic interpretation of the extremely successful Adversarially Guided Actor Critic (AGAC). My findings have potential implications for learning in a time-constrained safety-critical control context, e.g. the control of optical systems where new data needs to be absorbed quickly while remaining robust with respect to both known “optimal” control algorithms and previous knowledge.

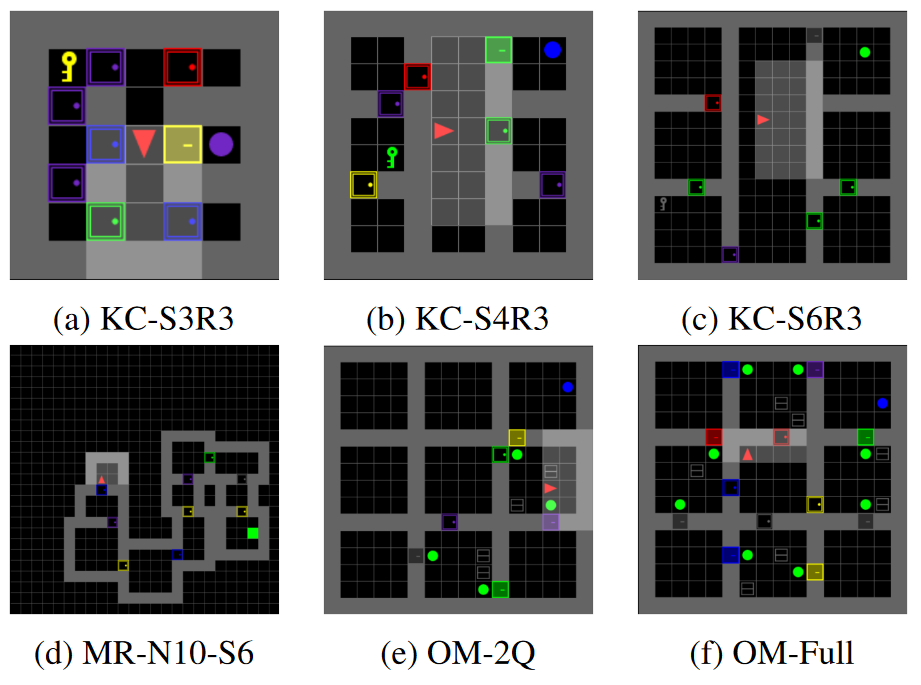

Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful approach for solving complex decision-making problems in various domains, including robotics, game-playing, and autonomous systems. However, the success of RL algorithms is often hindered by the challenges of hard exploration, sparse rewards, and partial visibility. Hard exploration refers to the problem of discovering optimal actions in a large state space, where only a small fraction of states are visited during training. Sparse rewards, on the other hand, refer to the difficulty of providing informative feedback to the agent, where the reward signal is infrequent or only available at the end of an episode. Finally, partial visibility refers to the challenge of incomplete or noisy observations of the environment, which limits the agent’s ability to learn a comprehensive policy.

In some problems, external rewards may not be easily defined or not available at all, and it may be necessary for the agent to learn from intrinsic rewards that arise from the environment or the task itself. This approach is called intrinsic motivation or curiosity-driven learning, where the agent is motivated to explore the environment and learn new skills for the sake of novelty or curiosity. Without effective strategies for dealing with hard exploration, sparse rewards, and partial visibility, current RL agents fail to learn effective policies and take an impractically long time to converge.